In the previous issue, we have discussed the first 3 components of the COMPETE© Model and how it can help businesses increase sales revenue and reduce operating costs. We now look at the remaining components.

In the previous issue, we have discussed the first 3 components of the COMPETE© Model and how it can help businesses increase sales revenue and reduce operating costs. We now look at the remaining components.

COMPETE

COMPONENT 4: PLANNING

Old habits die hard, some say. But to a large extent, it is true. Past competitive behaviour of management follow them even as they change employment to helm another organisation. Do not rest on our laurels, as a wise saying goes. Unfortunately, successes of past strategies are commonly re-cycled with mixed results. Observing their recruitment policies will also throw some light on their human resource build-up, possibly indicating a new strategic move. Models typically used to narrow down your opponent’s options include Porter’s generic strategies, Ansoff’s product/market growth and Lynch’s expansion method matrixes.

Porter’s Generic Strategies

Which strategy will you employ against your competitors?

The 3 generic strategies proposed by Porter is being the overall cost leader, be differentiated or be narrowly focused.

Being a Cost Leader, you are in the position to determine whether to match your competitors’ pricing or go below them, and still able to make superior profit margins. This deters potential new entrants from coming into your niche market. Buyer and supplier power will also minimally affect your business. To be the lowest cost producer, you need to examine your entire value chain and see where costs might be further reduced. The risks of this strategy are the loss of cost competitiveness through technological changes, obsolescence, domestic inflation, exchange rate fluctuations, etc.

Being a Differentiated Leader, you can either match your competitors’ pricing or go higher and still be able to secure supernormal profits. Thus price wars may be avoided. This again deters potential new entrants from coming into your niche market. Buyer and supplier power will also minimally affect your business. Like the lowest cost producer, you need to examine the entire value chain to ensure that premium pricing is justified. The risks of this strategy are that the additional differentiation might not justify the pricing premium; brand loyalty purchases are affected by external economic slow-down; and customers become more discerning and sophisticated, thus will go for more no-frills selections.

There are few firms that can be a cost or differentiation leader, the rest must be focused. Hence the third strategy, being cost focused or differentiation focused. The risks of this strategy are that there is no guarantee that broad target firm do not develop economies of scale and move into the lowest cost sector; competitors discover sub-market segments, differences between needs and tastes narrows, etc.

This decision-making model enables you to decide on your unique strategy, depending on your position audit findings and the potential for the future. Even if you aim to adopt a waitand- see attitude, there are risks involved, as the market is not standing still.

Do the same for your rivals, determining their cost structure, product and brand perception, and strategies. You will realise that some rivals are keener than most, while others are not really your rivals at all. As in any other models, there are limitations to Porter’s Generic Strategies model. But suffice to say that the main points of the model are still valid.

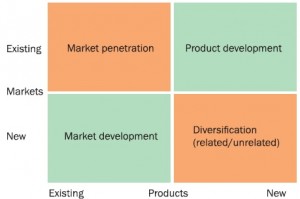

Ansoff’s Product/Market Growth

Having decided whether to be a lowest cost producer or a differentiated one, you next need to choose the strategic options available to you.

Market penetration is a strategy used with existing products for existing markets. Tactical steps include price reductions, promotional and distribution support, acquisition of a rival, and small product refinements. This strategy is frequently used by retailers in Singapore but unfortunately the retailing sector is already very saturated and margins are extremely slim.

Product development is the strategy employed to capitalise on existing customer base with new product offerings. Tactical steps include research and development of new products, acquisition of new production rights, joint product developments, etc. Continuous software upgrades is a good example. Perhaps it is a good idea for retailers to bring in new products on a regular basis to stir up new consumer demand.

Market development refers to using existing products to enter new markets, locally or regionally. New markets might include different customer segments, consumer and industrial buyers, new regions and locations, and foreign markets. Singapore’s popiah skins and curry puffs are good examples of using local favourites to venture abroad. This strategy will likely succeed when the firm has a unique product technology, reaps economies of scale, new markets are not too different, and buyers in the new market are intrinsically profitable.

Diversification involves exploring into related and unrelated industries. Related includes forward (securing distribution channels) and backward (securing raw materials source) vertical integration. McDonald’s produces its own potatoes in Russia when they could not find a suitable supplier in the early 1990s. Unrelated diversification enables spreading of business risks across a wide range of industries, perhaps to escape a mature or declining industry. A fine example is Wing Tai Holdings. Previously a major garment manufacturer, it has now diversified into property development, branded clothing retailing, and food and beverage.

Lynch’s Expansion Method

Following on from the strategies you have selected for growing your sales revenue, this matrix will suggest methods that you can consider for expansion.

These strategies are self-explanatory. There are of course technicalities, benefits and drawbacks associated with each method of expansion.

COMPETE

COMPONENT 5: EXPECTED BEHAVIOUR

There are at least 4 different ways for your competitors to respond to your strategic moves. Kotler (1997) classified them as follows.

The laid-back competitor basically does not respond to any competitive manoeuvres. On the other hand, the tiger competitor is the complete opposite. He will always respond aggressively to send a stern message to its competitors.

As the name implies, the selective competitor responds selectively, perhaps based on limited resources available.

Finally, the stochastic competitor is unpredictable. He may or may not respond, and his response can be minimal or drastic.

At times, it is also important to observe and analyse the rational for non-response from your competitors. It might be that the market may no longer be worth defending. Due to limited resources, they might have been redeployed to the next generation products or services instead of defending near obsolete range. Perhaps they are confident of retaining their customers and thus are not worried.

When a competitor cannot exit easily without incurring extensive losses, they are forced to stay and fight to the end in the hope of salvaging something. In such situations, he will be aggressive. Thus cost structures are important. Generally put, competitors with high fixed-cost, unit costs or exit costs will respond

aggressively to competitive threats.

COMPETE

COMPONENT 6: TRIED AND TESTED

Adolf Hitler did not study the historical records of previous attempts to conquer Russia. Hence, his mighty army fell to the cold Russian winter in the same manner as Alexander the Great and Napoleon Bonaparte did.

You need to keep track of the tried and tested strategies of your competitors. Are they any good? Have there been any management changes since then? Are they inclined to repeat historical mistakes or are they willing to fine-tune old strategies to suit current scenarios?

COMPETE

COMPONENT 7: EXPECTED OUTCOMES

This follows on from the previous component. What was the success rate? Are they expected to recur? If so, what is their sustainable competitive advantage? Did we anticipate these outcomes, especially with the tools provided? If not, do we go back to component 1 again for further analysis?

Thus this completes the Competitor Analysis process. The author wishes to encourage all business owners or franchise operators to think strategically so that they will be able to ask insightful questions and make full use of their management accountant’s expertise to help their businesses increase sales revenue and reduce operating costs.

Wayne Soo

CPA Singapore, CA (Malaysia), FCCA(UK), FCMA (UK), PNA (Australia) MSID, MBA (Manchester), Certified Fraud Examiner (CFE) USA Certified Management Consultant (CMC) Singapore.

Managing Partner

H W SOO & Co

Fiducia LLP

Certified Public Accountants

1 Goldhill Plaza

#03-35 Podium Block

Singapore 308899.

T: (65) 68468376

F: (65) 62346306

W: www.fiducia-llp.com

W: www.integrita.org

Email Wayne at

hw.soo@pacific.net.sg

Wayne Soo gained his more than 16 years of auditing, accounting, management and financial experience initially with a Top 4 public accounting firm (both in Malaysia and Singapore). He founded his own firm in 2005, and has been an active audit, tax, business advisory and insolvency practitioner and trainer since then. H W SOO & Co is on the audit panel of both the National Council of Social Service (NCSS) and Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports (MCYS).

To date, Wayne has been intimately involved in providing assurance, tax and advisory services to clients in many different industries. He holds 5 professional accounting qualifications and is a member of national accounting bodies in Singapore, Malaysia, UK and Australia.